I’ve spent decades watching building codes shift, tighten, and sometimes overreach. I’ve seen windows move from rattling double-hungs to low-E coated marvels, and I’ve watched insulation standards creep upward until our walls perform like refrigerators. It’s been a steady evolution, not a revolution.

But lately I’ve noticed something different. Younger homebuyers—Gen Z and Millennials—aren’t just asking for better performance, they’re expecting it. And they’re doing it at a time when many in the construction industry still argue that “good enough” from the year 2000 should be good enough forever.

This article digs into why the generational attitudes are so different today, and what the consequences would be—economically and environmentally—if we still built homes like it’s 2000. Spoiler: it wouldn’t be pretty.

The Generational Split Over Building Performance

Ask a Baby Boomer what matters in a new home and the answers are predictable: price, location, warranty, and square footage. Ask Gen Z and you’ll hear something you wouldn’t have heard 20 years ago:

“How efficient is it? Will it lower my bills? What’s its carbon footprint?”

It’s not that young buyers are trying to save the planet all by themselves—they just don’t want to buy a house that feels outdated the moment they close on it. They’ve grown up in a world where cars last 200,000 miles, phones update themselves overnight, and appliances whisper instead of roar. To them, a drafty house with U-0.50 windows feels like a dial-up internet connection.

Why Gen Z and Millennials Favor Higher Standards

Affordability through operating cost.

These buyers are stretched. Between student loans, rent, and eye-watering first-home prices, they look at monthly expenses differently. A home that saves $30–$60 a month in utilities matters. High-performance thin-triple windows and airtight construction aren’t luxury to them; they’re survival.

Climate awareness.

This generation wasn’t raised on a steady diet of “the ice caps may melt someday.” They’ve lived through wildfire seasons, smoke-filled skies, heat waves, and $400 electric bills. Efficiency isn’t political—it’s practical.

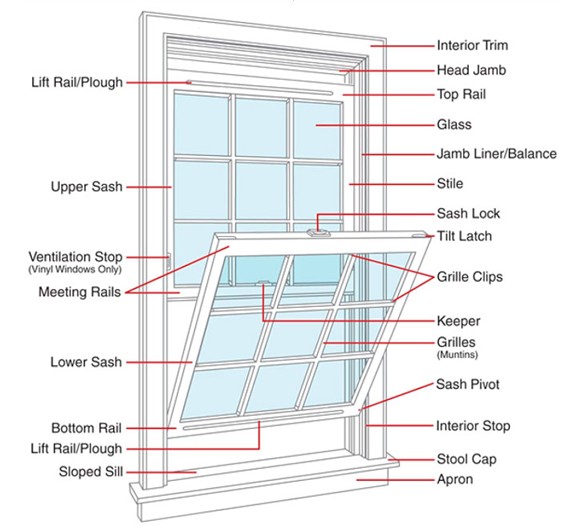

Comfort and quiet.

Thin triples, airtight frames, and better insulation mean no more cold wall syndrome, no more condensation, and far less street noise. A quiet, even-temperature home feels like an upgrade you can live inside.

Resale protection.

They know that in ten years, anything built to 2000 standards will be the equivalent of buying a house with aluminum wiring or a single-pane sunroom: a problem waiting to be discounted.

What Boomers and Gen X Think

Older buyers aren’t against better performance; they’re against higher prices. They’ve watched building codes add cost every two or three years. They remember when low-E glass was a novelty and when R-13 walls were considered “tight.”

Their mindset is simple:

“If you can show me the cost increase is small and the benefit is real, I’m in.”

Most will support 2027 standards—especially if the energy savings roughly offset the higher mortgage payment. And in many regions, it will.

What If We Built Every Home to the Year 2000 Code?

Now we get to the real gut punch. Let’s imagine the code books froze in time—no advancements, no improvements, nothing beyond what a builder in 2000 would have done.

Here’s what it would look like.

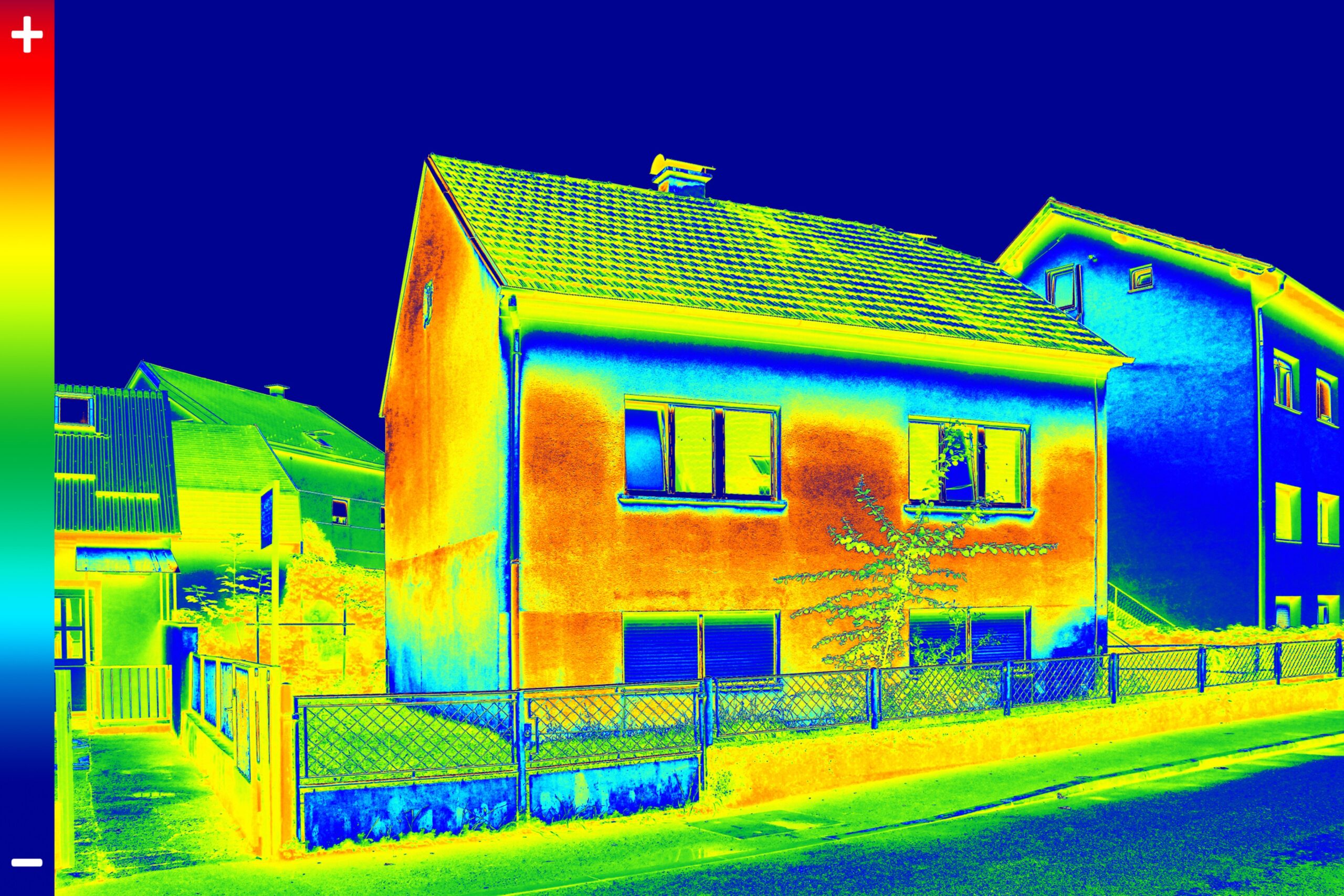

1. Windows That Bleed Energy

In 2000, windows with U-values around 0.55 were considered normal.

Compare that with today’s:

- 0.28–0.30 for modern vinyl/thermally broken frames

- 0.18–0.22 for thin triples

- 0.12–0.16 for quad-glazed Passive-House units

A 2000-era window leaks about twice as much heat as a 2024 window and nearly four times as much as a 2027 thin-triple standard.

The cost?

Hundreds of extra therms or thousands of extra kWh a year—per home.

Multiply that by the nearly one million new homes built every year, and you’re looking at an energy disaster.

2. A Blower Door Test? What’s That?

Most homes in 2000 leaked like a screen door in a hurricane.

It wasn’t unusual to see:

- 7–12 ACH50 (air changes per hour at pressure)

- No testing at all in many states

Today, the standard is:

- 3–5 ACH50 nationally

- 1–2 ACH50 in efficient or offsite-built homes

A 2000-built home could lose $500–$1,200 worth of heated or cooled air every year, simply through leaks.

Worse, the HVAC system must be oversized just to compensate, which means:

- Bigger units

- More noise

- Shorter lifespan

- Higher carbon output

3. Insulation That Would Get a Failing Grade Today

Let’s compare typical insulation:

Component 2000 Code Modern Code (2024–2027) Attic R-30 R-49 to R-60 Walls R-13 R-20+R-5 or R-21 Basement/Crawl Minimal R-10 to R-15 continuous Air Sealing Optional Mandatory

A house is a system. If one part is weak—especially windows or walls—the whole energy profile collapses.

4. Total Environmental Impact: A Disaster on Repeat

If every home built in the next decade followed 2000 codes:

- New homes would emit 30–45% more CO₂ every single year.

- We’d need millions more megawatt-hours of grid generation.

- Heat pumps wouldn’t perform well enough in leaky homes, slowing national electrification efforts.

- Utility bills would skyrocket, especially in northern and desert climates.

- States with aggressive energy goals (CA, MA, NY) would fail them by a mile.

DOE modeling shows that building 1 million homes per year to 2000 standards would add the same carbon output as putting 7–10 million extra gasoline cars on the road annually.

That’s not a rounding error.

That’s a national setback.

The 2027 Reality: Higher Standards Are Coming Anyway

Whether the industry likes it or not, we’re moving toward:

- U-value targets around 0.28–0.30

- Thin-triple or quad-pane glass becoming mainstream

- Thermally broken, airtight frames

- Tighter blower-door limits

- Stronger insulation requirements

And here’s the twist:

The cost increases are not the scary numbers we heard 10–15 years ago.

A full upgrade to 2027 specs typically adds:

- $2,000–$6,000 to a new home, or

- About 0.5–1.5% to the sale price

Mortgage impact:

- $15–$45/month

Energy savings:

- $15–$25/month

When you do the math, the cost of a 2027-quality envelope and glazing package is now close to net-neutral—and the comfort gains are undeniable.

Why Younger Buyers Will Drive This Shift Faster Than the Codes Will

Gen Z and Millennials are entering their prime buying years. They’re also:

- The largest two generations in American history

- The most environmentally aware

- The most cost-conscious

- The most demanding about comfort and quality

They’re not willing to buy the drafty, under-insulated homes their parents bought. They’re not shy about walking away from builders who aren’t up to date. And they increasingly view a good thermal envelope as essential—not optional.

In other words:

The market will enforce 2027 performance levels even if the code cycle moves slowly.

The Takeaway for Offsite, Modular, and Panelized Manufacturers

This is the moment when offsite can shine.

Factories already excel at:

- Tight air sealing

- Consistent installation

- Better window alignment

- Precision framing that supports higher R-values

- Lower waste and better QC

Younger buyers want the efficiency and comfort that factory-built homes naturally deliver. The only barrier is awareness.

If the industry leans into this generational shift—through better messaging, marketing, and education—we could stop competing on price alone and start competing on performance, comfort, and lifetime value.

My Final Thoughts

If we built today’s homes to the standards of the year 2000, the environmental and economic fallout would be enormous. But the good news is younger buyers won’t let that happen. They don’t want their first home to feel obsolete, noisy, drafty, or expensive to operate.

They want better—and the industry is finally in a place where “better” no longer breaks the bank.

If the offsite world steps forward and claims this space, 2027 won’t be a burden.

It’ll be an opportunity.

.

With over 9,000 published articles on modular and offsite construction, Gary Fleisher remains one of the most trusted voices in the industry.

.

CLICK HERE to read the latest edition

Contact Gary Fleisher