Then and Now

Every once in a while, it pays to stop and take a deep breath before comparing yesterday’s housing costs to today’s. Few examples make that point clearer than the Sears “Martha Washington,” one of the most elegant kit homes offered in the 1920s. Its catalog price—$3,727—was within reach for many middle-class families of the era. Fast-forward a century, and that same house, if built to today’s codes and sold by an investor, would likely be priced somewhere between $600,000 and $800,000, or even higher. The contrast is not just striking; it is a solemn reminder of how far we have allowed housing affordability to drift from the reach of ordinary people.

The Kit Home Revolution

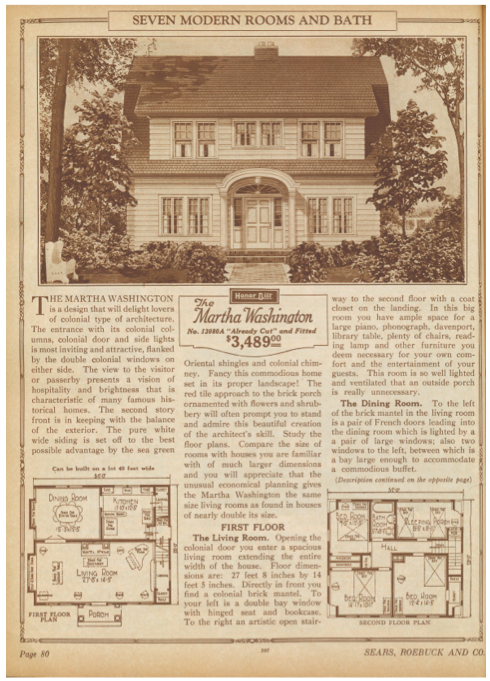

Between 1908 and 1940, Sears, Roebuck & Co. sold an estimated 70,000 to 75,000 kit homes through its mail-order catalogs. These homes were shipped by rail, delivered in thousands of numbered parts, and assembled by homeowners or local contractors. The company promised “a house for every man’s purse and purpose.”

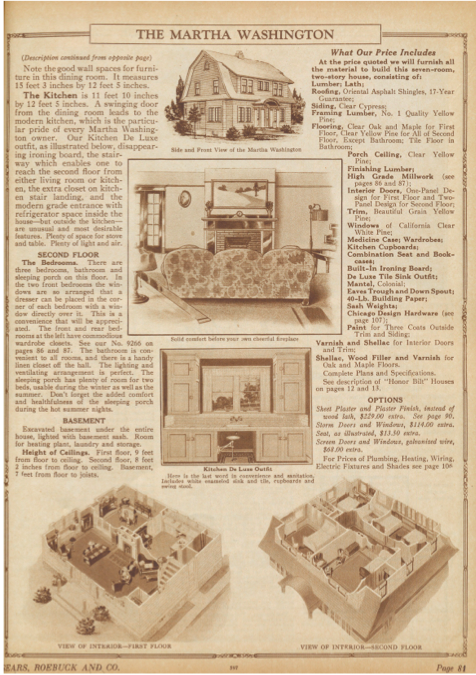

The “Martha Washington” was one of the more luxurious models. A two-story Colonial Revival with broad porches, elegant detailing, and four bedrooms, it embodied the aspirations of an expanding middle class. For $3,727, a family received not only the lumber and nails but also windows, doors, paint, and instructions. Many families built these homes themselves, enlisting friends and neighbors in barn-raising fashion. Others hired local carpenters, paying modest sums to complete the assembly. The result was a sturdy, stylish home at a fraction of the cost of traditional custom construction.

Inflation Alone Doesn’t Tell the Story

If we merely adjust $3,727 for inflation, the number seems quaint but not outrageous. By the most reliable measures, one dollar in 1925 is equal to about $18.46 today. That means the kit’s cost translates to roughly $69,000 in current purchasing power.

At first glance, this seems manageable. In fact, one might even argue it would make housing affordable again. But the real story is more complicated—and far more sobering. Inflation alone ignores the mountain of modern requirements: labor costs, building codes, permitting, inspection fees, and the steep price of land.

Adding the Contractor’s Touch in the 1920s

Even in the 1920s, not everyone wanted—or was able—to build a house with their own hands. Investors in particular would have turned to contractors, who added a markup for labor and expertise. Historical records suggest that contracting added 25–50 percent to the kit’s base price. That would push the all-in construction cost of the “Martha Washington” to around $4,600 to $5,600.

Factor in land, excavation, and utility hookups, and the resale price to a family buyer might have landed between $6,000 and $7,000. In today’s dollars, that equals roughly $110,000 to $130,000. Even then, the house was an attainable dream for the middle class, and investors could turn a modest profit without pushing the home beyond the reach of ordinary workers.

The Modern Investor’s Reality

Now imagine an investor attempting the same play in 2025. The starting point is no longer $200 for a boxcar of lumber but a construction marketplace defined by soaring costs.

Lumber and materials: The average construction cost for a mid-range custom home in many parts of the United States now runs between $200 and $300 per square foot. For a 2,000-square-foot home, that equates to $400,000 to $600,000 before a single inspection fee is paid.

Permitting and codes: Unlike the 1920s, today’s homes must meet complex codes for electrical, plumbing, energy efficiency, hurricane resistance, and fire safety. These codes are important for safety but add significant expense, often tacking on 10–20 percent to the base cost.

Land and site work: A century ago, farmland on the edge of town could be had for a few hundred dollars. Today, even modest suburban lots can run tens of thousands of dollars—or far more in desirable markets. Add in excavation, grading, driveways, septic or sewer hookups, and the bill climbs higher.

Contractor fees and overhead: Modern contractors operate in a tightly regulated environment with insurance costs, OSHA compliance, and skilled-labor shortages. Their overhead is built into bids, which are typically far higher than those of their 1920s counterparts.

Profit margin: Finally, an investor today cannot escape the need to mark up the project for profit. That margin often runs 15–25 percent to account for financing costs, risk, and opportunity loss.

Taken together, these realities push the resale price of a newly built “Martha Washington” replica into the $600,000 to $800,000 range. In higher-end locations or with premium finishes, the figure could easily top $900,000.

A Century of Drift

This comparison highlights a brutal truth: in 100 years, the cost of a solid, middle-class home has ballooned far beyond inflation. What was once a reachable dream for a young family—the ability to own a handsome four-bedroom home on a modest income—has become an investment play reserved for those with deep pockets.

The kit home represented efficiency, accessibility, and optimism. The modern equivalent represents complexity, regulation, and exclusion. While today’s homes are safer, more energy-efficient, and technologically advanced, they are also priced at levels that exclude vast swaths of working families.

Then vs. Now – The Price of a “Martha Washington”

| Category | 1920s Sears Catalog | 2025 Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Base kit price | $3,727 | ~$69,000 (inflation-adjusted only) |

| With contractor labor | $4,600–$5,600 | $450,000–$600,000 (construction only) |

| Finished resale price (with land/utilities) | $6,000–$7,000 | $600,000–$800,000 (with land, permits, codes) |

| Investor’s profit margin | Modest—10–20% | 15–25% markup on hundreds of thousands |

| Typical middle-class affordability | Within reach of teachers, clerks, farmers | Out of reach for most middle-income households |

Why the Disparity Matters

It is tempting to shrug and say, “Times change.” But the stakes are far higher. Housing is not just another commodity; it is the foundation of stability, family life, and community building. When the baseline price of a family home reaches three-quarters of a million dollars, society loses more than affordability. We lose the sense that homeownership is attainable through honest work and determination.

The Sears kit homes of the 1920s gave working Americans the dignity of a well-built house. Today’s costs push that dignity out of reach. Investors who once could make a modest margin selling affordable homes now find themselves forced into markets that serve only the upper middle class and above.

The Sobering Lesson

The absurd journey of the Sears “Martha Washington”—from $3,727 to $700,000—tells us more than any white paper or government study about the failures of our housing system. A century of inflation, regulation, and financialization has turned what was once attainable into a luxury.

We should not romanticize the past; early 20th-century America had its own inequities and housing shortages. But it is worth asking why a model that worked—mass-produced, standardized housing sold at affordable prices—has not found its modern equivalent. We have traded simplicity for complexity, accessibility for profit margins, and affordability for bureaucracy.

The old Sears catalogs promised “a house for every man’s purse and purpose.” That promise feels hollow today. Until we reckon with why a $69,000 kit home equivalent must now sell for nearly a million dollars, we will continue to chase affordability without ever catching it.

.

With over 9,000 published articles on modular and offsite construction, Gary Fleisher remains one of the most trusted voices in the industry.

.

CLICK HERE to read the latest edition

Contact Gary Fleisher