Every few years, someone at a conference, a webinar, or a LinkedIn thread drops the statistic like a mic:

“Sweden builds 80 to 85 percent of its homes in factories. The U.S. builds about 3 percent. What are we doing wrong?”

It’s a fair question. It’s also the wrong one.

Because Sweden didn’t decide to do modular better than the United States. Sweden reorganized housing as an industrial product, and then spent half a century reinforcing that decision until it became normal. The U.S., on the other hand, organized housing as a custom, site-based craft industry and never really stopped—no matter how many factories we built along the way.

To understand why Sweden’s numbers are so high, you have to stop thinking about modular as a construction method and start thinking about it as a national operating system.

First, Let’s Clear Up the 85 Percent Myth

When people hear “85 percent modular,” they picture volumetric boxes rolling off assembly lines like cars.

That’s not what Sweden does.

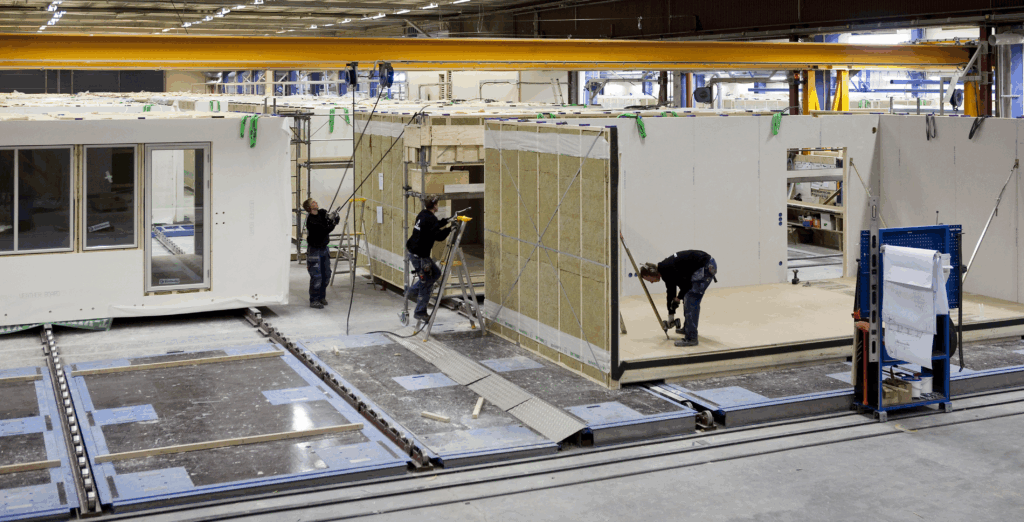

Most of Sweden’s factory-built housing falls under a broader category called industrialized construction. That includes:

- Closed wall panels

- Floor and roof cassettes

- Volumetric modules

- Highly standardized timber systems

In Sweden, factory-built doesn’t mean one thing. It means anything that can be produced indoors, repeatedly, with predictable outcomes.

When you compare Sweden’s industrialized housing to the U.S.’s narrow definition of “modular,” you’re not comparing apples to apples. You’re comparing an ecosystem to a product category.

And ecosystems always win.

Sweden’s Turning Point Came from Crisis, Not Innovation

Sweden’s factory-first approach didn’t start as a cool idea. It started as a national emergency.

Between 1965 and 1974, Sweden launched what became known as the Million Programme, an ambitious plan to build one million homes in less than a decade. The country was facing:

- Severe housing shortages

- Rapid urbanization

- Limited skilled labor

- Harsh weather conditions

There simply weren’t enough tradespeople—or enough warm, dry days—to build that many homes conventionally.

So Sweden did something radical.

They stopped asking how to build houses and started asking how to manufacture housing.

Factories weren’t experiments. They were necessities.

And once the factories were built, something important happened: they didn’t disappear when the crisis ended.

They evolved.

Timber Was the Trojan Horse

If you want to understand Sweden’s success, follow the trees.

Sweden has a long history of timber construction, but more importantly, it invested heavily in engineered wood systems and precision manufacturing decades before most U.S. builders had ever heard the term “panelization.”

Timber housing in Sweden became:

- Standardized

- Engineered

- Repeatable

- Factory-friendly

Small single-family homes weren’t treated as custom projects. They were treated as products with options, much closer to manufactured housing thinking than American stick-built tradition—except executed at a much higher architectural and energy-performance level.

This matters because factories thrive on repeatability, not heroics.

Weather Made the Business Case Obvious

Sweden’s climate is brutal on construction schedules.

Short days. Long winters. Wet conditions. Tight seasonal windows.

In that environment, site-built inefficiency isn’t just annoying—it’s expensive and risky.

Factories solved real problems:

- Crews could work year-round

- Quality stayed consistent

- Schedules became bankable

- Waste dropped dramatically

In much of the U.S., builders still believe they can “build through it.” Sweden didn’t have that luxury.

So while American builders optimized around flexibility, Swedish builders optimized around certainty.

Banks noticed.

High Labor Costs Forced Productivity

Sweden doesn’t have cheap labor. And it never did.

That reality forced a mindset shift long before the U.S. started worrying about skilled labor shortages. When labor is expensive, you don’t ask how to hire more people—you ask how to need fewer labor hours per home.

Factories delivered that:

- Safer working conditions

- Fewer mistakes

- Less rework

- Higher output per worker

This wasn’t about replacing people. It was about respecting labor enough to stop wasting it.

In the U.S., we’re only now starting to have that conversation—and mostly because we’ve run out of options.

Standardization Isn’t a Dirty Word in Sweden

This might be the biggest cultural difference of all.

In Sweden, buyers are comfortable choosing from predefined product lines. Customization exists, but within controlled boundaries. The home is still “theirs,” but it isn’t reinvented from scratch every time.

That consumer mindset allows factories to:

- Lock designs

- Optimize processes

- Improve continuously

- Scale profitably

In the U.S., we still treat customization as a moral virtue. Every deviation feels justified. Every plan tweak is “just one more small change.”

Factories can’t survive that mindset.

Sweden Built the Entire Stack—Not Just Factories

Here’s what the U.S. often misses.

Sweden didn’t just build factories. It aligned:

- Codes

- Financing

- Design education

- Supply chains

- Builder expectations

The system supports industrialized housing from concept to occupancy.

In the U.S., modular factories often operate in spite of the system, not because of it. They fight zoning. They educate lenders. They retrain inspectors. They absorb inefficiencies that have nothing to do with production.

That friction keeps percentages low—no matter how good the factory is.

So Why Will the U.S. Probably Never Hit 85 Percent?

Let’s be honest.

The U.S. doesn’t need to become Sweden—and likely never will.

Here’s why.

First, our housing market is too fragmented. Fifty states. Thousands of jurisdictions. Endless local variation. Industrial systems hate fragmentation.

Second, American consumers still romanticize custom building. Even production builders market uniqueness, not standardization. That psychology is hard to unwind.

Third, our regulatory environment rewards site-built tradition, not industrial efficiency. Even when modular meets code, it often doesn’t meet comfort levels—politically or culturally.

Fourth, we’re trying to retrofit factories into a system that was never designed for them. Sweden built the system first. We’re trying to wedge factories into the cracks.

And finally, the U.S. modular industry often oversells the comparison instead of explaining the difference. When people believe we can “just be more like Sweden,” they underestimate how deep the structural divide really is.

The Better Question Isn’t “Why Aren’t We Sweden?”

The better question is:

What percentage makes sense for the U.S.—and under what conditions?

If we broaden our definition to include panelization, components, and hybrid systems, the U.S. could realistically reach 15–25 percent industrialized housing over time.

That would be transformational.

Not Swedish-level—but meaningful, profitable, and scalable.

Sweden didn’t win because it built more modules.

It won because it stopped pretending housing wasn’t an industrial product.

When the U.S. is ready to do the same—on its own terms—we won’t need to chase 85 percent.

We’ll finally start climbing out of 3.

CLICK HERE to read the latest edition

Contact Gary Fleisher