Profitability vs. Affordability

For all the lofty speeches about housing for everyone, the reality is that builders and developers follow the math. Land costs have soared, skilled labor is scarce, and interest rates remain stubbornly high. Against that backdrop, developers face a choice: put their money into modest homes that sell for tight margins, or invest in larger, higher-priced projects that deliver stronger returns. Almost every time, profitability wins.

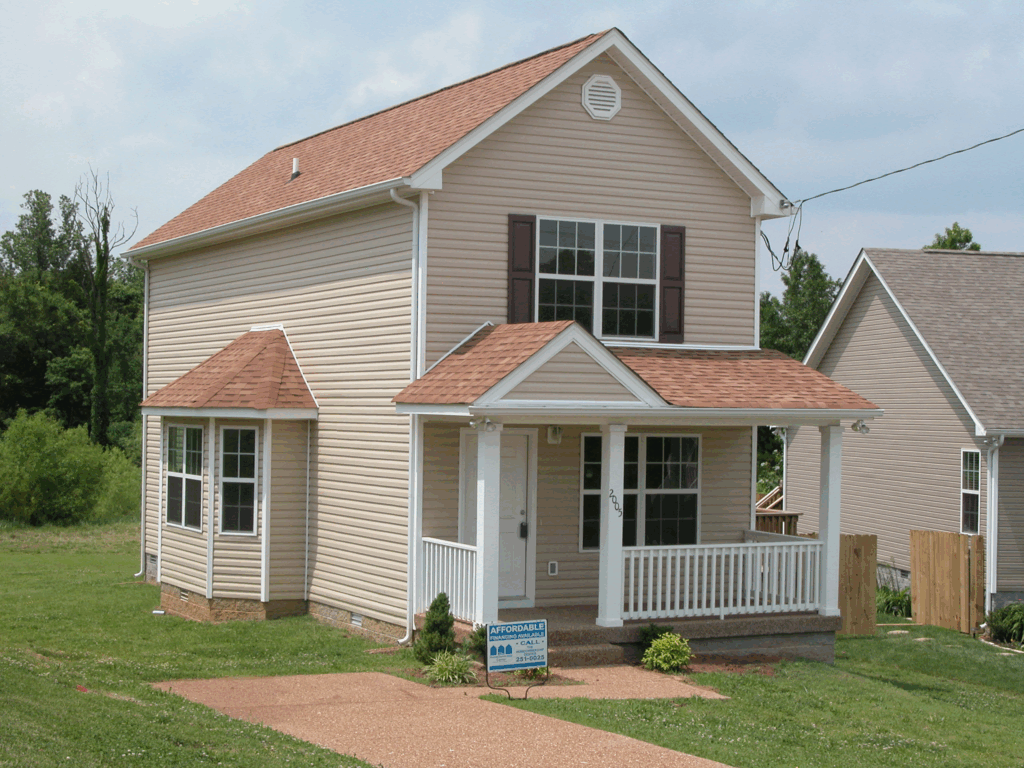

photo – Affordable Housing Resources, INC.

Affordable housing is not a charity venture. It is an economic puzzle that rarely adds up unless there are tax credits, government subsidies, or other incentives layered into the deal. Without that cushion, building truly affordable homes often means working harder for less. For most developers, especially those answering to shareholders or lenders, that’s not a calculation they can justify. And so the cycle continues—projects lean upscale, the affordable stock shrinks, and the gap between what people earn and what they can buy widens.

The Income Ratio Trap

For decades, affordability has been defined by a simple formula: no more than thirty percent of household income should go toward housing costs. But formulas don’t pay for lumber, land, or labor. Median wages in the U.S. have barely budged in real terms over the past 20 years, while the cost of constructing a single-family home has risen dramatically.

That thirty percent rule, once a lifeline, now feels like a trap. To fit within the ratio, homes have to shrink. In urban centers, “affordable” has morphed into micro-units—studios smaller than 400 square feet. In the suburbs, developers market accessory dwelling units (ADUs) or backyard cottages as the new starter homes. Even modular factories, built on the promise of efficiency, are turning out smaller footprints to hit affordability targets.

Affordable housing still exists on paper, but in practice, it looks far different than the comfortable starter homes of the 1970s or even the compact townhomes of the 1990s. For younger generations, “affordable” now means compromise: less space, fewer options, and often a longer commute.

The Coming Wave of Standardization

If affordability is to survive at scale, housing production must move from being a craft to an industry. That shift is already underway in modular and offsite factories. Companies like BotBuilt in North Carolina are using robotics to build wall panels, roof trusses, and floor cassettes with startling precision. In California, Factory_OS is delivering entire apartment units assembled in factories on Mare Island, dramatically cutting timelines for affordable housing projects in the Bay Area.

photo – The New York Times

Standardization is the common denominator in these efforts. The more repetitive the design, the more efficient the process becomes. Automation thrives on repetition. That means the future of affordable housing will not be filled with endless customizations. Instead, it will resemble the auto industry: models and trims, designed once and built thousands of times.

This doesn’t have to be bleak. Standardization, done well, can lead to durable, attractive, and highly energy-efficient housing. But it does mean homeowners may have fewer opportunities to personalize layouts. Instead of picking from endless options, the choice may be between Plan A or Plan B.

A Global Experiment in Scale

The United States isn’t alone in this shift. In the UK, one modular factory has gained attention for employing prisoners on day release, with one in three staff members working under that program. Of the 31 prisoners who took part, 30 moved into permanent employment afterward. The experiment shows how modular housing can serve not only as a construction solution but also as a workforce rehabilitation model.

Meanwhile, in Asia, companies are pushing scale even further. In China, prefabricated apartment towers rise in weeks rather than months, built from standardized modules produced in high-volume factories. These projects reveal what’s possible when housing is treated as a product to be manufactured, rather than as a one-off construction project.

For U.S. builders watching these examples, the lesson is clear: affordability at scale will require not just new financing models, but an entirely new mindset about how homes are designed, built, and delivered.

The Shrinking Idea of Home

The most profound change may not be in how homes are built, but in how they are imagined. For generations, the image of affordable housing was a single-family home with a small yard, a driveway, and maybe a picket fence. It was never glamorous, but it was achievable.

Photo – Governing

That vision is fading. Affordable housing will continue, but it will exist more often in apartments, ADUs, and shared co-living spaces. Instead of backyards, residents will have shared courtyards. Instead of garages, they may have bike rooms. Affordability will be measured in access and efficiency rather than square footage.

For some, this may feel like loss. For others—especially younger generations—it may feel like a new kind of freedom. Smaller, standardized spaces can be easier to maintain, more environmentally sustainable, and less financially risky. The trade-off is individuality. The mass-produced home rarely carries the charm of a custom build, but it may be the only way forward.

The Role of Robotics and Automation

The question remains: is this the end of affordable housing in the U.S.? The answer depends on how quickly robotics and automation can be scaled. Without them, the economics are stacked against affordability. Labor shortages and material costs alone make traditional construction too expensive to deliver homes within the thirty percent income rule.

With robotics, however, the industry has a fighting chance. Automation can reduce waste, improve safety, and accelerate timelines. A factory line of robotic arms can frame walls or install windows in minutes, tasks that might take human crews hours. The savings from such efficiency could be the key to making smaller units truly affordable, not just in name but in practice.

This doesn’t mean robots will replace human workers. Instead, it points to a hybrid future, where humans and machines work together—machines handling repetitive tasks, while people bring the craftsmanship and problem-solving skills that no robot has mastered.

The Future of Affordability

We are not witnessing the end of affordable housing, but rather the end of a particular vision of it. The “starter home” as we once knew it is disappearing. What will take its place are smaller, more standardized, and more industrially produced units. The challenge for policymakers, developers, and communities is to ensure that these homes are not just cheaper, but also livable, dignified, and connected to the fabric of their neighborhoods.

Affordable housing in the coming decades will be built on new foundations—robotics, modularization, and standardization. It may not match the romantic image of a family home with a yard, but it will offer something equally vital: stability, security, and the possibility of ownership or long-term rental within reach of ordinary incomes.

The real question is whether society will accept this new definition of affordable, or continue to chase the dream of something that no longer exists.

.

With over 9,000 published articles on modular and offsite construction, Gary Fleisher remains one of the most trusted voices in the industry.

.

CLICK HERE to read the latest edition

Contact Gary Fleisher